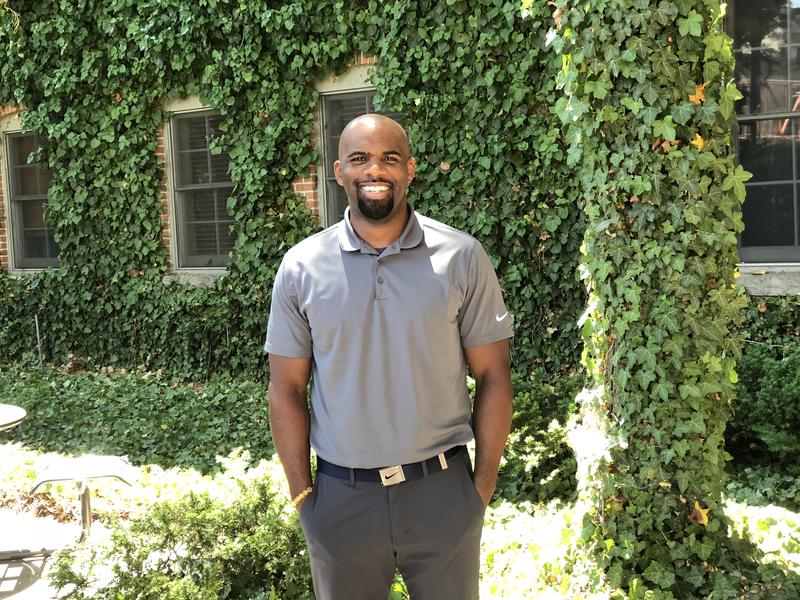

Passion, purpose and a love story: How Michigan’s Jevon Moore joined the fight around mental health in college sports is a feature story written for The Athletic Detroit. The main subject is Jevon Moore, an counselor and fellow in the U-M Athletic Department, detailing his life from football player who wondered why athletes struggled to now helping student-athletes on a daily basis. In it, Moore’s life is examined through the relationship with his wife, Stephanie, and how the Moore family landed in Ann Arbor. Below is an excerpt.

By Cody Stavenhagen

By Cody Stavenhagen

Moore liked the fact he was challenged around Stephanie. He liked the idea of personal growth. As a kid, he was always the friend who took notice when someone was acting strangely. He liked to ask people questions, to make them feel comfortable opening up. In college, he always wondered why some players made it and others, sometimes the most talented, ended up back at home after a year.

For a little while, he even went to counseling and learned more about coping mechanisms, thinking more about how he could best manage his own struggles. He had no idea how all this would later apply.

Stephanie was also chasing her own life and career, so that meant a year in London, then a move to Chicago for her master’s. Eventually, Moore decided to follow his passions. He quit his job and moved to Chicago to be with her. He planned to pursue a college coaching job, but that never quite happened. He worked as a bartender, then spent a summer working with a program called Freedom Schools. Around this time, he realized he might be able to make an even bigger impact away from coaching.

“I didn’t want to have to trick people into listening to me because I was your coach,” Moore said. “If I want to really help you and I tell you to do this, but then the next play you do something else, our relationship is affected. I wanted to pull the sport away from it. I wanted to say, ‘OK, I have nothing else to do with this other than your well-being.’”

The big break came when Stephanie applied to a Ph.D. program at the University of Michigan.

Thanks largely to his wife’s drive, Moore ended up in Ann Arbor, and he says he snuck his way into a job with the athletic department, working in community outreach. He’d take athletes to work with schools or help with events.

He talked with Greg Harden, Michigan’s renowned athletic counselor best known for performance work with Tom Brady, and the more they talked, Moore realized he could be best suited for a different line of work. Harden got his start in social work before Bo Schembechler hired him as a student-athlete counselor in 1986, a move that was well ahead of its time.

I didn’t want to have to trick people into listening to me because I was your coach. If I want to really help you and I tell you to do this, but then the next play you do something else, our relationship is affected. I wanted to pull the sport away from it. I wanted to say, ‘OK, I have nothing else to do with this other than your well-being.’ — Jevon Moore

Soon, Harden had Moore chasing a master’s degree in social work. Soon, Moore began working as a counselor. Chances are none of that happens if he doesn’t meet Stephanie.

“I could be doing engineering and building and making all this money and what have you,” Moore said. “But the things I would be engineering are used by people, and if people aren’t OK, then it doesn’t make sense to do all that.”

* * *

It’s Monday afternoon in the South Athletic and Performance Center, and representatives for Athletes Connected are meeting to discuss plans for the summer and into the fall.

There are no suits or ties, no people with fancy titles giving detailed, academic dissertations on mental illnesses. Instead, it’s six people in a small conference room with bad lighting, working together to make a difference. A large portion of the June meeting centered on how they should make their magnets – a long slogan or a short one? — to pass out and raise awareness. The same group that is taking part in innovative research is still a small shop.

When Moore speaks in the meeting, he tends to command attention. He’s giving a breakdown of a restorative yoga program Athletes Connected is trying to get off the ground. He uses expressive claps and hand motions, and the energy of the room picks up noticeably. The yoga program has potential, but the logistics remain a challenge.

Zoom out, and the issues Athletes Connected faces remain towering concepts. The group has met with U-M coaches, who are supposedly interested and most often understanding. But implementing effective mental care in an athletic environment isn’t always easy. Too often, performance and mental health are made out to be competing ideas.

“Everyone’s as educated about it as they are scared of it,” Moore said.

One of the leaders of the program is Will Heininger, a former Michigan defensive lineman who has been at the forefront of the group’s media coverage. One of the first videos Athletes Connected produced focused on Heininger and his battle with major depression in college. Now Heininger works in U-M’s Depression Center in addition to being an outreach coordinator for Athletes Connected. He does plenty of public speaking and spends time dreaming up a world where mental care is treated no differently than physical care in college athletic programs.

“It’s still the tip of the iceberg,” Heininger said. “Look at where the strength and conditioning programs are, as opposed to when they had one weight room and one coach.”

Read the rest of the story on The Athletic.

By Cody Stavenhagen

By Cody Stavenhagen