We share an excerpt from an ESPN.com story about a writer, Ivan Maisel, and the family of Tyler Hilinski, Washington State’s quarterback who died by suicide in January 2018. The Maisel and Hilinski families both experienced the heartbreak of losing a family member to suicide.

By Ivan Maisel

I came of age in the wake of Woodward and Bernstein, when young journalists were taught to be as neutral as the painted highway stripe. After nearly four decades as a sportswriter, I have learned to negotiate a middle ground between my training and my life experience. Some stories demand more of the latter.

Mark and Kym Hilinski started a foundation in their son Tyler’s memory, Hilinski’s Hope, to fund mental health programs for Division I athletes. (AP Photo/Chris Carlson)

Almost three years earlier, my son Max ended his life. He was a college junior, the second of three children, 21 years old, hundreds of miles away from home.

Like a winemaker trying to create a structured red, how much of the skin you leave in the juice changes the color and character of the final product. I’ve got a lot of skin in this one.

There’s often an immediate intimacy among parents whose children have ended their lives. We get it. The loss of a child is an awful subject, so awful that it makes people uncomfortable. They don’t know what to say. One of the many secrets of The Club No One Wants to Join is that we love to talk about the children we’ve lost. Talking about them keeps them present.

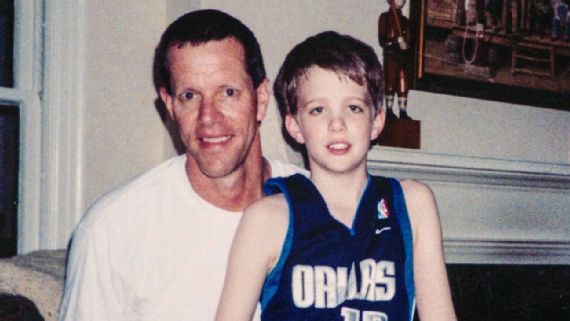

Ivan and Max Maisel in 2004 (Courtesy Maisel Family)

When you live with the awful every moment of every day, the awful becomes everyday. It is no longer so daunting. When someone told me I was living “a parent’s worst nightmare,” I responded, “No, you wake up from nightmares.”

The first time I called Mark Hilinski, Tyler’s father, we spoke for 1 hour, 10 minutes. “I had never talked to anybody — in my spot,” Mark said later, with a mirthless laugh. “Got emails, got letters, got cards, read a ton. … But that was the first time I had talked to anybody that kinda sat over here, and I appreciated it.”

Mark’s wife, Kym, Tyler’s mother, sounded a note of grace. “I’m actually happy that [people] can’t understand,” she said, “because I would never, ever want anyone to really understand what you and I are going through.”

Mark is a bear of a man, personable in the way that most successful salesmen are personable. He is a traditional American Dad. He responds to problems in the stereotypically American Dad way: looking to fix them. Except that this problem, the biggest that he and Kym have ever faced, can’t be fixed.

He hates that he can’t fix the problem, and he hates that he feels self-pity because he can’t fix the problem, and once you go down that rabbit hole it can be a long time before you see sunlight again.

He understands that he is not the first father to lose a son. He understands we live in a world where bad things happen. He and Kym recently attended a memorial for a 20-year-old struck by lightning.

“If you can muster it, that’ll put some perspective on you quick,” Mark said, “but it doesn’t lessen the sadness for me.”

Read the rest of the story on ESPN.com.

Dave Ingles is starting to tell his story.

Dave Ingles is starting to tell his story.