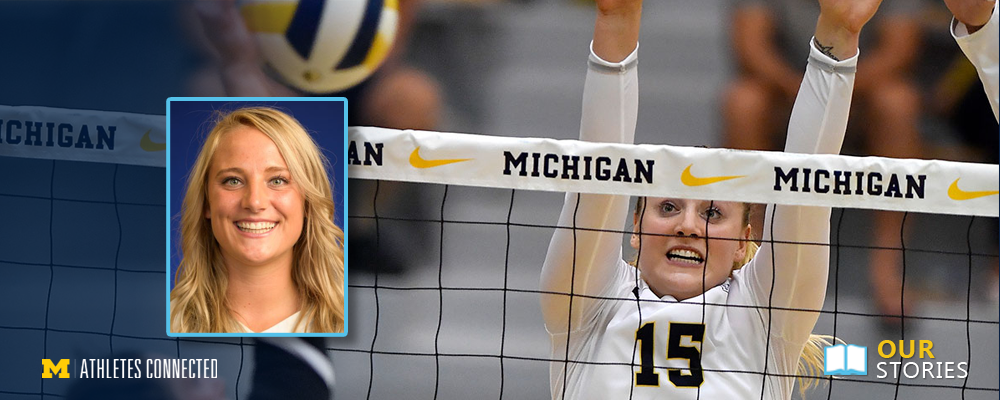

By Sydney Wetterstrom, Outside Hitter, U-M Volleyball

During my time at Michigan I was surrounded by amazing athletes, students and leaders. Some were All-Americans or academic weapons, but most were just really pleasant people you wanted to surround yourself with.

Looking back now, that makes sense because the University of Michigan is known for bringing together and building the “leaders and best.”

The adjustment from high school to college can be a difficult transition for some athletes, especially at Michigan where we have come from being big fish in a small pond throughout high school to becoming a small fish in an ocean. This can be overwhelming, stressful and frustrating. For me personally, I stumbled, tumbled and fell hard. Very, very hard.

I ignored my stress, picked up poor coping strategies and reverted back to bad habits. My stress became a distraction and interfered with my performance on the court.

It was scary, but getting my diagnosis was the first time I did not feel like my feet were dragging cement blocks.

One day in a pre-practice session with my volunteer assistant coach, I broke down crying. An utterly beautiful mess of tears and snot came running down my cheeks and nose. She comforted me and recommended I use the resources provided by the Athletics Counseling Team (ACT).

But I did not listen to her advice.

I felt ashamed and embarrassed. I remember telling myself, “This is so silly, nothing is wrong with me. I am in the best shape of my life,” yet I still felt incomplete, broken and lost. I was so far in denial that it was not until I attempted to take my own life, did I get the help I needed.

Even then I was still against seeking help. It was not until a teammate said “If you do not get help for yourself, get help for me because I am worried for you.” I was hospitalized and treated for severe anxiety and major depressive disorder.

It was scary, but getting my diagnosis was the first time I did not feel like my feet were dragging cement blocks. Truth had lifted the 200 pounds of denial off my shoulders. I had no idea that the reason I had been feeling so poorly was because of my mental health.

I was honest with my coaches and created an open dialogue with my teammates. I let those around me know that I had been struggling with mental health.

I soon realized that many of my peers had faced challenges with mental health, too. This made me realize the importance of mental health, but also the stigma that comes along with it.

I soon realized that many of my peers had faced challenges with mental health, too. This made me realize the importance of mental health, but also the stigma that comes along with it.

I wondered how many other people had been in my shoes? Who felt embarrassed, shameful and nervous for reaching out for issues related to their mental health? Who else had felt the fear of judgement, or felt that it was a sign of weakness?

All of these thoughts and experiences led me to the belief that it is necessary for all student-athletes to be comfortable asking for help before it is too late.

Mental health is equally as important as physical health. Through the resources in the athletic department, I found it not only easier for student-athletes to receive care for mental health, but also found it easier to remove the negative bias surrounding it. Supporting someone in their time of need, whether it is a sprained ankle or anxiety, is the only way a student-athlete will return to the competition in a timely manner.

My experiences showed me that support will enable an individual to feel confident and comfortable. This confidence and comfort will launch them into success. When someone feels supported they are more likely to succeed.

When someone feels supported they are more likely to succeed. I found community and support to be critical on and off the court

I found community and support to be critical on and off the court. With the help of numerous peers I was able to participate in and create a number of student-athlete organizations within athletics.

During my junior year, I created Student-Athlete Sexual Health (SASH) with fellow student-athlete Sam Roy, who is a member of the women’s gymnastics team. With the endorsement from the ACT, Sam and I established a support group for survivors of sexual assault. Individuals were provided a safe and confidential place to discuss their own personal story with emphasis on rebuilding and healing post-sexual trauma(s); along with ACT’s Abigail Eiler, we thoughtfully identified resources and skill-building activities focused on improving our overall health and wellness across each domain of our lives.

Sam and I were also both members of SAAC, and were the heads of the mental health subcommittee our senior year. As mental health liaisons, and with the help of the ACT, we had Athlete Ally come in for a two-day training with staff, coaches and student-athletes.

Athlete Ally is a nonprofit that advocates for the LGBTQ+ community in athletics. After the onsite training and student-athlete feedback, we structured an Athlete Ally chapter on campus, which has become a place for students that are a part of the LGBTQ+ community and allies to come together and support one another. The group is making strides to remove the stigma surrounding LGBTQ+ athletes in sport.

My way of leading this was to make sure everyone felt included and unconditionally loved and accepted. Additionally, as the mental health liaisons, Sam and I coordinated a mental health public service announcement to be displayed at all sporting events. I believe athletes can perform at their highest level when they feel comfortable in their own skin!

I plan to attend Florida State in the fall of 2020 to pursue a Master in Social Work (MSW). There, I hope to continue to break down the barriers that surround mental health.

Once I have attained my degree, I hope to implement SASH programs across the country at universities designated for student-athlete survivors of sexual abuse.

Currently, Sam and I are working towards establishing SASH as a nonprofit organization. We have also created a workbook for individuals or groups to use. My dream is for SASH resources to be utilized by survivors at all schools that have NCAA sports, in order to ensure they feel supported and to assist them in their healing journey.

Know that everyone is trying their best. Support your teammates and let them support you. We all have faced adversity.

Consequently, when a hand is reached out to pull you up, take it. It only makes challenges easier. Being a leader means to care for yourself and those around you genuinely; it means being the one to reach out to help pull others up, but also asking for help when you need it.

About the Author

About the Author

Sydney Wetterstrom was a four-year letterwinner for the U-M women’s volleyball team. Wetterstrom garnered three Academic All-Big Ten nods and started all 32 matches her senior year in 2019. Wetterstrom graduated from the University of Michigan with degrees in exercise science and Spanish. She is set to begin work on a Master of Social Work degree at Florida State in fall 2020 where she will compete on the beach volleyball team.

I soon realized that many of my peers had faced challenges with mental health, too. This made me realize the importance of mental health, but also the stigma that comes along with it.

I soon realized that many of my peers had faced challenges with mental health, too. This made me realize the importance of mental health, but also the stigma that comes along with it.  About the Author

About the Author

Q: What is your vision?

Q: What is your vision?